|

|

||||||||

|

|

| Home |

Volume 1: No. 4, October 2004

Suggested citation for this article: Howard VJ, Acker J, Gomez CR,

Griffies AH, Magers W, Michael M III, et al, for the Delta States Stroke

Consortium. An approach to coordinate efforts

to reduce the public health burden of stroke: the Delta States Stroke

Consortium. Prev Chronic Dis [serial online] 2004 Oct [date cited].

Available from: URL:

http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2004/

oct/03_0037.htm

Stroke is the third leading cause of death and a leading cause of disability in the United States, with a particularly high burden on the residents of the southeastern states, a region dubbed the “Stroke Belt.” These five states — Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee — have formed the Delta States Stroke Consortium to direct efforts to reduce this burden. The consortium is proposing an approach to identify domains where interventions may be instituted and an array of activities that can be implemented in each of the domains. Specific domains include 1) risk factor prevention and control; 2) identification of stroke signs and symptoms and encouragement of appropriate responses; 3) transportation, Emergency Medical Services care, and acute care; 4) secondary prevention; and 5) recovery and rehabilitation management. The array of activities includes 1) education of lay public; 2) education of health professionals; 3) general advocacy and legislative actions; 4) modification of the general environment; and 5) modification of the health care environment. The Delta States Stroke Consortium members propose that together these domains and activities define a structure to guide interventions to reduce the public health burden of stroke in this region.

Stroke is the third leading cause of death and a leading cause of disability in the United States (1). Unfortunately, the burden of stroke does not fall proportionately on the nation’s population. Residents of the southeastern states, a region dubbed the “Stroke Belt,” carry a particularly high burden. The Stroke Belt has been defined on the basis of high rates of stroke mortality, but the causes of high stroke mortality are a matter of debate and uncertainty (2,3). Although the boundaries of the Stroke Belt are not distinct, eight southern states are considered to compose its core: North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Louisiana.

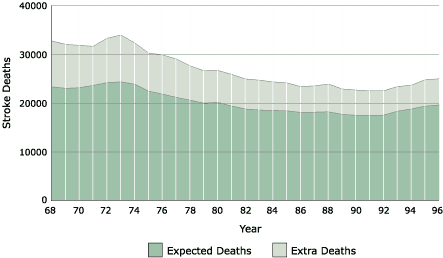

The magnitude of the public health burden imposed by the Stroke Belt is overwhelming. Figure 1 shows the number of deaths from stroke in the eight-state region from 1968–1996. During this 29-year period, 780,385 total deaths resulted from stroke in this region. The expected number of deaths from stroke can be calculated by applying the national stroke death rate to the population of the region, resulting in an expected 585,836 total deaths from stroke during 1968–1996. The difference of 194,549 deaths represents the “extra” stroke deaths, or approximately 6708 extra deaths on average annually. Although stroke incidence data are not available, the extra number of incident stroke events in the region each year can be approximated by dividing the number of extra deaths each year (6708) by the case fatality rate (approximately 30%), resulting in 22,363 extra stroke events each year. The mean lifetime cost of ischemic stroke in the United States is estimated to be $140,048 (in 1999 dollars), which includes inpatient care, rehabilitation, and follow-up care (4). These data suggest that the annual public health burden imposed by the Stroke Belt is more than $3.1 billion dollars. (Note that this is not the burden of stroke in the region, but rather the extra costs associated with the increased stroke risk in the region.)

Figure 1. Number of annual deaths from stroke in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Arkansas, 1968–1996. The darker portion shows the number of deaths from stroke that would have occurred if the death rate from stroke were the same as for the remainder of the nation, while the lighter area represents the “extra” deaths above national rates.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently published A Public Health Action Plan to Prevent Heart Disease and Stroke (5), a comprehensive plan to reduce the burden of stroke and heart disease. One of the five major components of the proposed strategy is to encourage “engaging in regional and global partnerships [to] multiply resources and capitaliz[e] on shared experience” (5). The importance of developing partnerships in the southeastern United States to reduce the burden of stroke is evident, given the immense public health burden of stroke in the region. This need gave rise to the Tri-States Stroke Consortium, established in 1997 to coordinate the efforts of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia (6). In 2002, the Delta States Stroke Consortium (DSSC) was formed to coordinate the efforts of the remaining five states in the Stroke Belt — Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Louisiana. This consortium includes representatives of state health departments, academic scientists, health care professionals, advocacy groups, pharmaceutical and other industry representatives, and stroke survivors. At the first meeting of the DSSC, held March 13–14, 2003, a plan for organizing efforts to reduce the burden of stroke in the region was developed and is summarized in this report.

The DSSC developed a context for planning interventions to reduce the public health burden of stroke based on a two-dimensional model. The first dimension is based on the observation that stroke is not an event, but rather a process that begins with developing risk factors and continues through caring for stroke survivors. The second dimension represents the array of activities that can be implemented to reduce the burden of stroke. Each of these dimensions is summarized below.

The public health burden of stroke results from a process that begins in childhood (some would suggest prior to childhood), continues to adulthood, continues to the stroke event, and then to the subsequent care of the stroke survivor. The DSSC has divided this process into five domains. Within each domain, opportunities exist to reduce the burden of stroke.

1. Risk factor prevention and control

Prevention of stroke, as well as of most chronic diseases, has been shown

to be the most cost-effective approach for reducing the public health burden

of disease (7). The broad field of prevention is increasingly considered as

being subdivided into two major domains: 1) primordial risk factor prevention

and 2) risk factor control.

Primordial risk factor prevention, or preventing individuals from ever developing the risk factor, is clearly the best way to control the risk factor (8). Many risk factors for stroke, such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity, have roots in childhood. Other risk factors, such as smoking, have roots in late adolescence. The first opportunity to reduce the burden of stroke is to intervene to reduce the development of risk factors.

There are, however, ample opportunities to reduce the burden of stroke after risk factors develop by improving the identification and control of those risk factors. For example, hypertension is the risk factor with the largest population-attributable risk: approximately 25% of strokes are attributable to the risk factor hypertension alone (9). While the number of hypertensive patients receiving appropriate diagnosis and management has improved dramatically, 31% of hypertensive patients are still unaware of their hypertension, and 69% of diagnosed hypertensive patients still do not control their condition adequately (10). Furthermore, benefits could be gained by better detection and control of other risk factors, including diabetes, atrial fibrillation, cigarette smoking, and other vascular risk factors (9,11,12).

2. Identification of stroke signs and symptoms and

encouragement of appropriate responses

While some consider tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) to be the only

acute treatment for stroke, many other approaches, including hydration and

blood pressure control, can improve the outcome of stroke and thereby reduce

the subsequent burden of events. The effectiveness of these alternatives is

supported by evidence showing that stroke patients have better outcomes when

they receive stroke-unit care rather than general hospital care (13). However, the

efficacy of these treatments is likely increased by the ability to intervene

early during the stroke event. It is critical that the stroke is quickly

identified and that it is perceived as a medical emergency that should be

managed by professionals; hence, the burden of stroke can be reduced by

improvements in the identification of strokes and in the decision making by

the stroke victim and those witnessing the event. Specifically, it is critical

that the public recognize stroke as a 911 emergency and that stroke

victims be transported to the hospital as quickly as possible.

3. Transportation, Emergency Medical Services (EMS) care, and acute care

After the stroke is identified and 911 is contacted, the outcome of the

stroke patient can be improved by prompt transport to an appropriate medical

facility and delivery of appropriate care during the acute phase of the event.

Effective transport is related to, but not solely determined by, the transport

time from initial 911 call to emergency room delivery. Decisions must be made

about the facility to which the patient should be taken and the kind of

treatment that should be delivered during transport. In addition, the burden

of stroke can be reduced by appropriate treatment after the patient arrives at

the medical facility.

4. Secondary prevention

Stroke has a high rate of recurrence. The recurrence rate within 30 days for

all cerebral infarcts in the Stroke Data Bank is 3.3%, and the one-year

cumulative rate of death or recurrent infarction is 15.3% (14). Other studies

have found the risk of recurrent stroke to be 8% in the first year and 12%

after two years (15-17). Many first neurologic events have transient effects

or minor long-term deficits; however, these patients are at elevated risk

for subsequent major stroke. Many proven treatments reduce the subsequent risk

of stroke, including risk factor management involving lifestyle changes,

medical management, and surgical interventions (12,18).

5. Recovery and rehabilitation management

After a stroke has occurred, rehabilitation therapies can increase the stroke

survivor’s

independence and quality of life, which have a direct

impact on the quality of life of the survivor’s family and caregivers and

reduce the cost of post-stroke care.

The five domains discussed above provide opportunities to intervene to reduce the burden of stroke through an array of activities. The DSSC formed a working group for each domain to ensure that all opportunities and activities were considered. The Table shows a matrix that couples examples of activities with a specific domain. Clearly, certain activities may be more or less appropriate for each domain; however, use of this matrix ensures that all potential activities for each domain are considered.

A brief description of each general activity suggested by the DSSC is provided below.

1. Education of lay public

Perhaps the most promising of all activities to reduce the burden of stroke

are efforts to educate the lay public. Educating the general public raises

awareness of 1) lifestyle choices that lead to the development and control of

risk factors, 2) stroke signs and symptoms, and 3) appropriate actions when

signs and symptoms occur. Positive changes in lifestyle choices are associated

with risk reduction. Education of the public also emphasizes the importance

of obtaining and complying with rehabilitation efforts. The literature is rich

with documentation of the lay public’s lack of knowledge about the signs and symptoms of

stroke (19-21), and there is an equally disturbing lack of knowledge in other

domains such as risk factors (19,21), EMS care

(22,23), and recovery and rehabilitation (24).

2. Education of health care professionals

Not only does the lay public lack knowledge about stroke prevention and

care but health care professionals also have gaps in knowledge about

opportunities to reduce the burden of stroke. Opportunities to improve the

knowledge and training of health care providers include educating them about

1) lifestyle choices that prevent the development of risk factors; 2) better

controls for existing risk factors; 3) appropriate guidance when initial signs

and symptoms are reported; 4) actions that reduce the chances of subsequent

strokes; and 5) potential gains offered by rehabilitation.

3. General advocacy and legislative actions

Another mechanism for reducing the burden of stroke is a highly focused

effort for advocacy and legislative changes. Primordial risk factor

prevention activities could include, for example, modification of public

school lunches and urban design to encourage physical activity. An activity to

promote primary control of risk factors could include public assistance for

blood pressure medication. General advocacy activities could include the

recruitment of lay opinion leaders to raise the awareness of stroke signs and

symptoms. Legislative actions with an impact on the acute care of stroke

patients should include encouraging the establishment of stroke centers (25).

Finally, advocacy and legislative actions can reduce subsequent stroke and

provide rehabilitation opportunities by ensuring access to services following

the stroke event.

4. Modification of the general environment

Modifying the general environment is a potentially powerful tool in

reducing the burden of stroke. Such activities include development of employee

education programs, appropriate EMS signage, and home alterations to

facilitate the return home of a stroke survivor.

5. Modification of the health care environment

Finally, there is the opportunity to modify the medical environment,

including EMS transport, which should be designed

to route stroke patients to hospitals equipped and ready to provide acute care

as well as access to computed tomography (CT) imaging and rehabilitation

services.

The DSSC is organized into five working groups, with the emphasis of each group corresponding to one of the domains described in this report. The goal in defining these domains is to incorporate the entire spectrum of the stroke process, which places such a heavy burden on the United States, particularly in the southeastern states. Each working group developed an array of activities that have the potential to impact the public health burden of stroke.

Developing the list of potential activities in each of the domains, however, is only the first step. Each activity will be rated by a subcommittee both on its potential impact and the feasibility of its implementation. Subsequently, the DSSC aims to implement activities with a high potential impact and an acceptable feasibility in an ongoing effort to reduce the burden of stroke.

The Delta States Stroke Consortium was initially supported through a grant from the Cardiovascular Health Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) within the Community Health Promotion Program, and is subsequently supported by the CDC under a grant agreement with the Cardiovascular Health Branch of the Alabama Department of Public Health.

Corresponding author: Virginia J. Howard, MSPH, Assistant Professor of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 210F Ryals Public Health Building, 1665 University Blvd, Birmingham, AL 35294-0022. Telephone: 205-934-7197. E-mail: vjhoward@uab.edu.

Author affiliations: Joe Acker, MPH, Birmingham Regional Emergency Medical Services System, Birmingham, Ala; Camilo R. Gomez, MD, Sean R. Orr, MD, Alabama Neurological Institute, Birmingham, Ala; Ada H. Griffies, MPH, Max Michael III, MD, George Howard, DrPH, School of Public Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Ala; Wanda Magers, MPA, Mississippi State Department of Health, Jackson, Miss; Martha Phillips, PhD, James M. Raczynski, PhD, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, Ark; John E. Searcy, MD, Alabama Medicaid Agency, Montgomery, Ala; Richard M. Zweifler, MD, University of South Alabama, Mobile, Ala.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors’ affiliated institutions. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by any of the groups named above.

Privacy Policy | Accessibility This page last reviewed March 30, 2012

|

|