|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

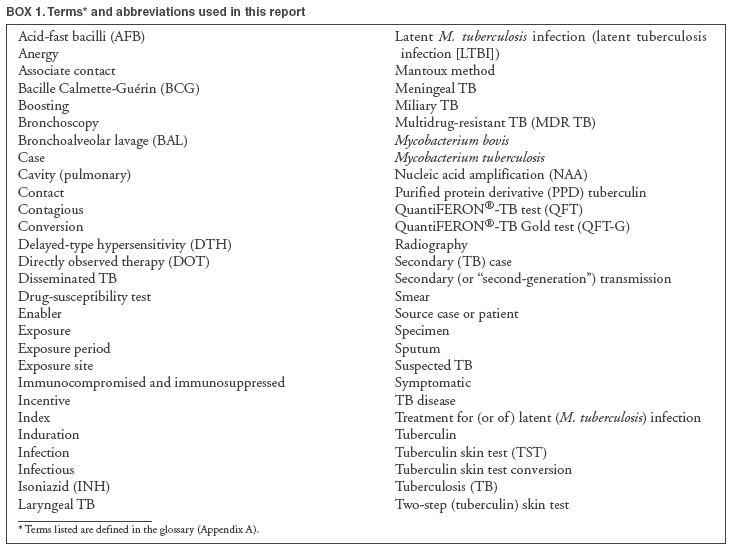

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: mmwrq@cdc.gov. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Guidelines for the Investigation of Contacts of Persons with Infectious TuberculosisRecommendations from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDCThe material in this report originated in the National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention, Kevin Fenton, MD, PhD, Director, and the Division of Tuberculosis Elimination, Kenneth G. Castro, MD, Director. Corresponding preparer: Zachary Taylor, MD, National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention, CDC, 1600 Clifton Road, NE, MS E-10, Atlanta, GA 30333. Telephone: 404-639-5337; Fax: 404-639-8958; E-mail: ztaylor@cdc.gov. SummaryIn 1976, the American Thoracic Society (ATS) published brief guidelines for the investigation, diagnostic evaluation, and medical treatment of TB contacts. Although investigation of contacts and treatment of infected contacts is an important component of the U.S. strategy for TB elimination, second in priority to treatment of persons with TB disease, national guidelines have not been updated since 1976. This statement, the first issued jointly by the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC, was drafted by a working group consisting of members from both organizations on the basis of a review of relevant epidemiologic and other scientific studies and established practices in conducting contact investigations. This statement provides expanded guidelines concerning investigation of TB exposure and transmission and prevention of future cases of TB through contact investigations. In addition to the topics discussed previously, these expanded guidelines also discuss multiple related topics (e.g., data management, confidentiality and consent, and human resources). These guidelines are intended for use by public health officials but also are relevant to others who contribute to TB control efforts. Although the recommendations pertain to the United States, they might be adaptable for use in other countries that adhere to guidelines issued by the World Health Organization, the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, and national TB control programs. IntroductionBackgroundIn 1962, isoniazid (INH) was demonstrated to be effective in preventing tuberculosis (TB) among household contacts of persons with TB disease (1). Investigations of contacts and treatment of contacts with latent TB infection (LTBI) became a strategy in the control and elimination of TB (2,3). In 1976, the American Thoracic Society (ATS) published brief guidelines for the investigation, diagnostic evaluation, and medical treatment of TB contacts (4). Although investigation of contacts and treatment of infected contacts is an important component of the U.S. strategy for TB elimination, second in priority to treatment of persons with TB disease, national guidelines have not been updated since 1976. This statement, the first issued jointly by the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association (NTCA) and CDC, was drafted by a working group consisting of members from both organizations on the basis of a review of relevant epidemiologic and other scientific studies and established practices in conducting contact investigations. A glossary of terms and abbreviations used in this report is provided (Box 1 and Appendix A). This statement provides expanded guidelines concerning investigation of TB exposure and transmission and prevention of future cases of TB through contact investigations. In addition to the topics discussed previously, these expanded guidelines also discuss multiple related topics (e.g., data management, confidentiality and consent, and human resources). These guidelines are intended for use by public health officials but also are relevant to others who contribute to TB control efforts. Although the recommendations pertain to the United States, they might be adaptable for use in other countries that adhere to guidelines issued by the World Health Organization, the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, and national TB control programs. Contact investigations are complicated undertakings that typically require hundreds of interdependent decisions, the majority of which are made on the basis of incomplete data, and dozens of time-consuming interventions. Making successful decisions during a contact investigation requires use of a complex, multifactor matrix rather than simple decision trees. For each factor, the predictive value, the relative contribution, and the interactions with other factors have been incompletely studied and understood. For example, the differences between brief, intense exposure to a contagious patient and lengthy, low-intensity exposure are unknown. Studies have confirmed the contribution of certain factors: the extent of disease in the index patient, the duration that the source and the contact are together and their proximity, and local air circulation (5). Multiple observations have demonstrated that the likelihood of TB disease after an exposure is influenced by medical conditions that impair immune competence, and these conditions constitute a critical factor in assigning contact priorities (6). Other factors that have as yet undetermined importance include the infective burden of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, previous exposure and infection, virulence of the particular M. tuberculosis strain, and a contact's intrinsic predisposition for infection or disease. Further, precise measurements (e.g., duration of exposure) rarely are obtainable under ordinary circumstances, and certain factors (e.g., proximity of exposure) can only be approximated, at best. No safe exposure time to airborne M. tuberculosis has been established. If a single bacterium can initiate an infection leading to TB disease, then even the briefest exposure entails a theoretic risk. However, public health officials must focus their resources on finding exposed persons who are more likely to be infected or to become ill with TB disease. These guidelines establish a standard framework for assembling information and using the findings to inform decisions for contact investigations, but they do not diminish the value of experienced judgment that is required. As a practical matter, these guidelines also take into consideration the scope of resources (primarily personnel) that can be allocated for the work. MethodologyA working group consisting of members from the NTCA and CDC reviewed relevant epidemiologic and other scientific studies and established practices in conducting contact investigations to develop this statement. These published studies provided a scientific basis for the recommendations. Although a controlled trial has demonstrated the efficacy of treating infected contacts with INH (1), the effectiveness of contact investigations has not been established by a controlled trial or study. Therefore, the recommendations (Appendix B) have not been rated by quality or quantity of the evidence and reflect expert opinion derived from common practices that have not been tested critically. These guidelines do not fit every circumstance, and additional considerations beyond those discussed in these guidelines must be taken into account for specific situations. For example, unusually close exposure (e.g., prolonged exposure in a small, poorly ventilated space or a congregate setting) or exposure among particularly vulnerable populations at risk for TB disease (e.g., children or immunocompromised persons) could justify starting an investigation that would normally not be conducted. If contacts are likely to become unavailable (e.g., because of departure), then the investigation should receive a higher priority. Finally, affected populations might experience exaggerated concern regarding TB in their community and demand an investigation. Structure of this StatementThe remainder of this statement is structured in 13 sections, as follows:

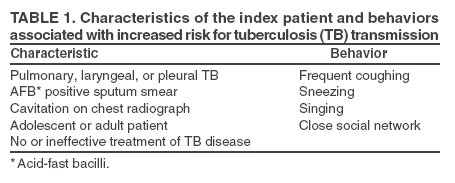

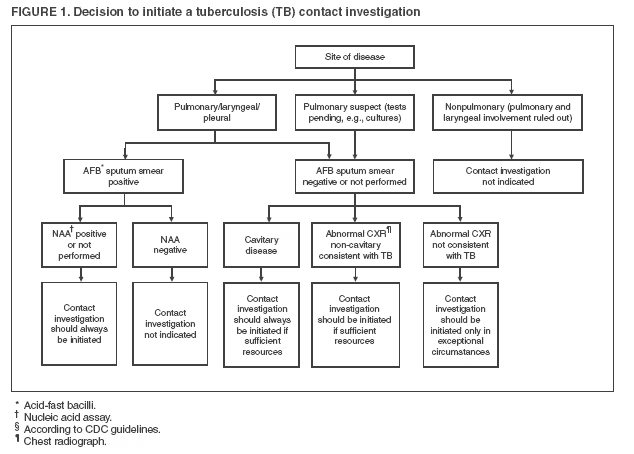

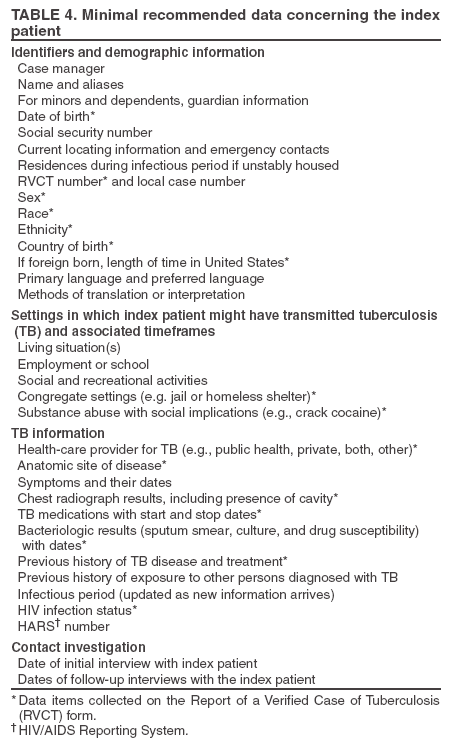

Decisions to Initiate a Contact Investigation Competing demands restrict the resources that can be allocated to contact investigations. Therefore, public health officials must decide which contact investigations should be assigned a higher priority and which contacts to evaluate first (see Assigning Priorities to Contacts). A decision to investigate an index patient depends on the presence of factors used to predict the likelihood of transmission (Table 1). In addition, other information regarding the index patient can influence the investigative strategy. Factors that Predict Likely Transmission of TBAnatomical Site of Disease With limited exceptions, only patients with pulmonary or laryngeal TB can transmit their infection (8,9). For contact investigations, pleural disease is grouped with pulmonary disease because sputum cultures can yield M. tuberculosis even when no lung abnormalities are apparent on a radiograph (10). Rarely, extrapulmonary TB causes transmission during medical procedures that release aerosols (e.g., autopsy, embalming, and irrigation of a draining abscess) (see Contact Investigations in Special Circumstances) (11--15) Sputum Bacteriology Relative infectiousness has been associated with positive sputum culture results and is highest when the smear results are also positive (16--19). The significance of results from respiratory specimens other than expectorated sputum (e.g., bronchial washings or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid) is undetermined. Experts recommend that these specimens be regarded as equivalent to sputum (20). Radiographic Findings Patients who have lung cavities observed on a chest radiograph typically are more infectious than patients with noncavitary pulmonary disease (15,16,21). This is an independent predictor after bacteriologic findings are taken into account. The importance of small lung cavities that are detectable with computerized tomography (CT) but not with plain radiography is undetermined. Less commonly, instances of highly contagious endobroncheal TB in severely immunocompromised patients who temporarily had normal chest radiographs have contributed to outbreaks. The frequency and relative importance of such instances is unknown, but in one group of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)--infected TB patients, 3% of those who had positive sputum smears had normal chest radiographs at the time of diagnosis (22,23). Behaviors That Increase Aerosolization of Respiratory Secretions Cough frequency and severity are not predictive of contagiousness (24). However, singing is associated with TB transmission (25--27). Sociability of the index patient might contribute to contagiousness because of the increased number of contacts and the intensity of exposure. Age Transmission from children aged <10 years is unusual, although it has been reported in association with the presence of pulmonary forms of disease typically reported in adults (28,29). Contact investigations concerning pediatric cases should be undertaken only in such unusual circumstances (see Source-Case Investigations). HIV Status TB patients who are HIV-infected with low CD4 T-cell counts frequently have chest radiographic findings that are not typical of pulmonary TB. In particular, they are more likely than TB patients who are not HIV-infected to have mediastinal adenopathy and less likely to have upper-lobe infiltrates and cavities (30). Atypical radiographic findings increase the potential for delayed diagnosis, which increases transmission. However, HIV-infected patients who have pulmonary or laryngeal TB are, on average, as contagious as TB patients who are not HIV-infected (31,32). Administration of Effective Treatment That TB patients rapidly become less contagious after starting effective chemotherapy has been corroborated by measuring the number of viable M. tuberculosis organisms in sputa and by observing infection rates in household contacts (33--36). However, the exact rate of decrease cannot be predicted for individual patients, and an arbitrary determination is required for each. Guinea pigs exposed to exhaust air from a TB ward with patients receiving chemotherapy were much more likely to be infected by drug-resistant organisms (8), which suggests that drug resistance can delay effective bactericidal activity and prolong contagiousness. Initiating a Contact InvestigationA contact investigation should be considered if the index patient has confirmed or suspected pulmonary, laryngeal, or pleural TB (Figure 1). An investigation is recommended if the sputum smear has AFB on microscopy, unless the result from an approved NAA test (Amplified Mycobacterium tuberculosis Direct Test [MTD], GenProbe,® San Diego, California, and Amplicor® Mycobacterium tuberculosis Test [Amplicor], Roche® Diagnostic Systems Inc., Branchburg, New Jersey) for M. tuberculosis is negative (37). If AFB are not detected by microscopy of three sputum smears, an investigation still is recommended if the chest radiograph (i.e., the plain view or a simple tomograph) indicates the presence of cavities in the lung. Parenchymal cavities of limited size that can be detected only by computerized imaging techniques (i.e., CT, computerized axial tomography scan, or magnetic resonance imaging of the chest) are not included in this recommendation. When sputum samples have not been collected, either because of an oversight or as a result of the patient's inability to expectorate, results from other types of respiratory specimens (e.g., gastric aspirates or bronchoalveolar lavage) may be interpreted in the same way as in the above recommendations. However, whenever feasible, sputum samples should be collected (through sputum induction, if necessary) before initiating chemotherapy. Contact investigations of persons with AFB smear or culture-positive sputum and cavitary TB are assigned the highest priority. However, even if these conditions are not present, contact investigations should be considered if a chest radiograph is consistent with pulmonary TB. Whether to initiate other investigations depends on the availability of resources to be allocated and achievement of objectives for higher priority contact investigations. A positive result from an approved NAA test supports a decision to initiate an investigation. Because waiting for a sputum or respiratory culture result delays initiation of contact investigations, delay should be avoided if any contacts are especially vulnerable or susceptible to TB disease (see Assigning Priorities to Contacts). Investigations typically should not be initiated for contacts of index patients who have suspected TB disease and minimal findings in support of a diagnosis of pulmonary TB. Exceptions can be justified during outbreak investigations (see Contact Investigations in Special Circumstances), especially when vulnerable or susceptible contacts are identified or during a source-case investigation (see Source-Case Investigations). Investigating the Index Patient and Sites of TransmissionComprehensive information regarding an index patient is the foundation of a contact investigation. This information includes disease characteristics, onset time of illness, names of contacts, exposure locations, and current medical factors (e.g., initiation of effective treatment and drug susceptibility results). Health departments are responsible for conducting TB contact investigations. Having written policies and procedures for investigations improve the efficiency and uniformity of investigations. Establishing trust and consistent rapport between public health workers and patients is critical to gain full information and long-term cooperation during treatment. Good interview skills can be taught and learned skills improved with practice. Workers assigned these tasks should be trained in interview methods and tutored on the job (see Staffing and Training for Contact Investigations and Contact Investigations in Special Situations). The majority of TB patients in the United States were born in other countries, and their fluency in English often is insufficient for productive interviews to be conducted in English. Patients should be interviewed by persons who are fluent in their primary language. If this is not possible, health departments should provide interpretation services. Preinterview PhaseBackground information regarding the patient and the circumstances of the illness should be gathered in preparation for the first interview. One source is the current medical record (38). Other sources are the physician who reported the case and (if the patient is in a hospital) the infection control nurse. The information in the medical record can be disclosed to public health authorities under exemptions in the Privacy Rule of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 (http://aspe.hhs.gov/admnsimp/pl104191.htm) (39). The patient's name should be matched to prior TB registries and to the surveillance database to determine if the patient has been previously listed. Multiple factors are relevant to a contact investigation, including the following:

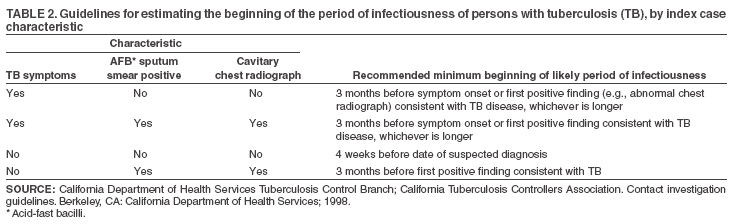

Determining the infectious period focuses the investigation on those contacts most likely to be at risk for infection and sets the timeframe for testing contacts. Because the start of the infectious period cannot be determined with precision by available methods, a practical estimation is necessary. On the basis of expert opinion, an assigned start that is 3 months before a TB diagnosis is recommended (Table 2). In certain circumstances, an even earlier start should be used. For example, a patient (or the patient's associates) might have been aware of protracted illness (in extreme cases, >1 year). Information from the patient interview and from other sources should be assembled to assist in estimating the infectious period. Helpful details are the approximate dates that TB symptoms were noticed, mycobacteriologic results, and extent of disease (especially the presence of large lung cavities, which imply prolonged illness and infectiousness) (40,41). The infectious period is closed when the following criteria are satisfied: 1) effective treatment (as demonstrated by M. tuberculosis susceptibility results) for >2 weeks; 2) diminished symptoms; and 3) mycobacteriologic response (e.g., decrease in grade of sputum smear positivity detected on sputum-smear microscopy). The exposure period for individual contacts is determined by how much time they spent with the index patient during the infectious period. Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR TB) can extend infectiousness if the treatment regimen is ineffective. Any index patient with signs of extended infectiousness should be continually reassessed for recent contacts. More stringent criteria should be applied for setting the end of the infectious period if particularly susceptible contacts are involved. A patient returning to a congregate living setting or to any setting in which susceptible persons might be exposed should have at least three consecutive negative sputum AFB smear results from sputum collected >8 hours apart (with one specimen collected during the early morning) before being considered noninfectious (42). Interviewing the PatientIn addition to setting the direction for the contact investigation, the first interview provides opportunities for the patient to acquire information regarding TB and its control and for the public health worker to learn how to provide treatment and specific care for the patient. Because of the urgency of finding other infectious persons associated with the index patient, the first interview should be conducted <1 business day of reporting for infectious persons and <3 business days for others. The interview should be conducted in person (i.e., face to face) in the hospital, the TB clinic, the patient's home, or a convenient location that accommodates the patient's right to privacy. A minimum of two interviews is recommended. At the first interview, the index patient is unlikely to be oriented to the contact investigation because of social stresses related to the illness (e.g., fear of disability, death, or rejection by friends and family). The second interview is conducted 1--2 weeks later, when the patient has had time to adjust to the disruptions caused by the illness and has become accustomed to the interviewer, which facilitates a two-way exchange. The number of additional interviews required depends on the amount of information needed and the time required to develop consistent rapport. Interviewing skills are crucial because the patient might be reluctant to share vital information stemming from concerns regarding disease-associated stigma, embarrassment, or illegal activities. Interviewing skills require training and periodic on-the-job tutoring. Only trained personnel should interview index patients. In addition to standard procedures for interviewing TB patients (43), the following general principles should be considered:

Proxy interviews can build on the information provided by the index patient and are essential when the patient cannot be interviewed. Key proxy informants are those likely to know the patient's practices, habits, and behaviors; informants are needed from each sphere of the patient's life (e.g., home, work, and leisure). However, because proxy interviews jeopardize patient confidentiality, TB control programs should establish clear guidelines for these interviews that recognize the challenge of maintaining confidentiality. Field InvestigationSite visits are complementary to interviewing. They add contacts to the list and are the most reliable source of information regarding transmission settings (17). Failure to visit all potential sites of transmission has contributed to TB outbreaks (25,44). Visiting the index patient's residence is especially helpful for finding children who are contacts (17,38). The visit should be made <3 days of the initial interview. Each site visit creates opportunities to interview the index patient again, interview and test contacts, collect diagnostic sputum specimens, schedule clinic visits, and provide education. Sometimes environmental clues (e.g., toys suggesting the presence of children) create new directions for an investigation. Certain sites (e.g., congregate settings) require special arrangements to visit (see Contact Investigations in Special Circumstances). Physical conditions at each setting contribute to the likelihood of transmission. Pertinent details include room sizes, ventilation systems, and airflow patterns. These factors should be considered in the context of how often and how long the index patient was in each setting. Follow-Up StepsA continuing investigation is shaped by frequent reassessments of ongoing results (e.g., secondary TB cases and the estimated infection rate for groups of contacts). Notification and follow-up communications with public health officials in other jurisdictions should be arranged for out-of-area contacts. The following organizations provide resources to make referrals for contacts and index patients who migrate across the U.S.-Mexican border between the United States and Mexico:

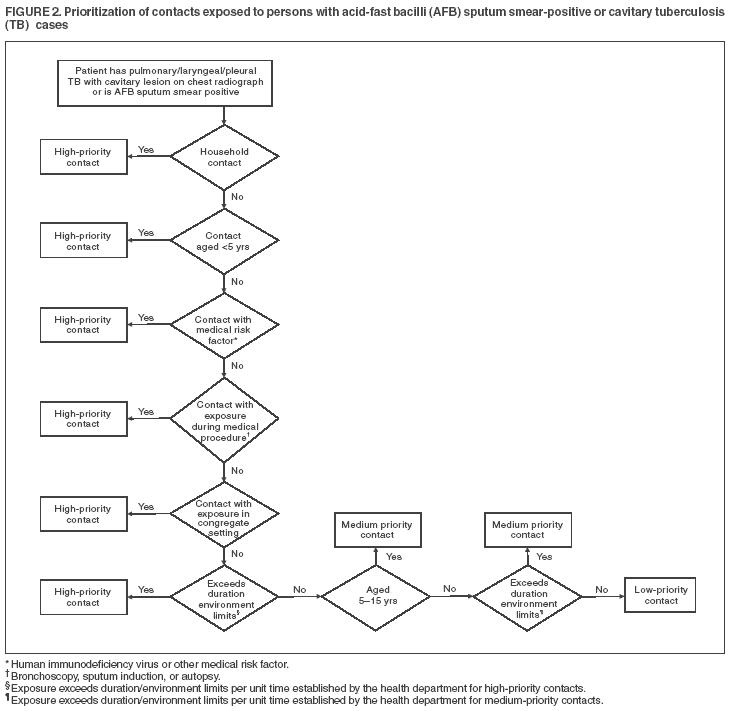

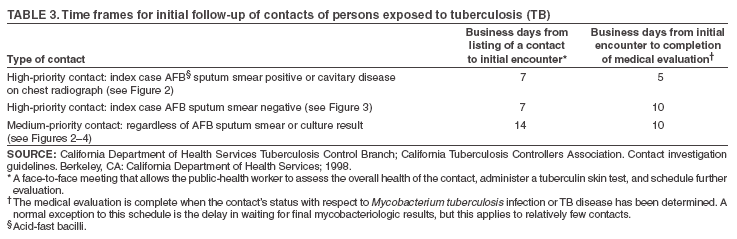

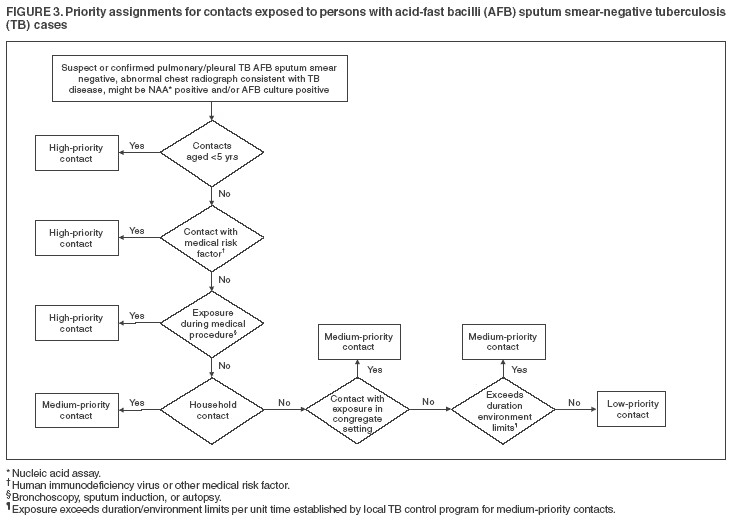

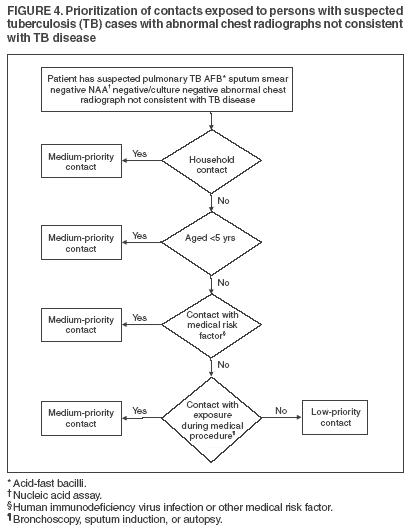

The investigation plan starts with information gathered in the interviews and site visits; it includes a registry of the contacts and their assigned priorities (see Assigning Priorities to Contacts and Medical Treatment for Contacts with LTBI). A written timeline (Table 3) sets expectations for monitoring the progress of the investigation and informs public health officials whether additional resources are needed for finding, evaluating, and treating the high- and medium-priority contacts. The plan is a pragmatic work in progress and should be revised if additional information indicates a need (see When to Expand a Contact Investigation); it is part of the permanent record of the overall investigation for later review and program evaluation. Data from the investigation should be recorded on standardized forms (see Data Management and Evaluation of Contact Investigations). Assigning Priorities to ContactsThe ideal goal would be to distinguish all recently infected contacts from those who are not infected and prevent TB disease by treating those with infection. In practice, existing technology and methods cannot achieve this goal. For example, although a relatively brief exposure can lead to M. tuberculosis infection and disease (45), certain contacts are not infected even after long periods of intensive exposure. Not all contacts with substantial exposure are identified during the contact investigation. Finally, available tests for M. tuberculosis infection lack sensitivity and specificity and do not differentiate between persons recently or remotely infected. Increasing the intensity and duration of exposure usually increases the likelihood of recent M. tuberculosis infection in contacts. The skin test cannot discriminate between recent and old infections, and including contacts who have had minimal exposure increases the workload while it decreases the public health value of finding positive skin test results. A positive result in contacts with minimal exposure is more likely to be the result of an old infection or nonspecific tuberculin sensitivity (46). Whenever the contact's exposure to the index TB patient has occurred <8--10 weeks necessary for detection of positive skin tests, repeat testing 8--10 weeks after the most recent exposure will help identify recent skin test conversions, which are likely indicative of recent infection. For optimal efficiency, priorities should be assigned to contacts, and resources should be allocated to complete all investigative steps for high- and medium-priority contacts. Priorities are based on the likelihood of infection and the potential hazards to the individual contact if infected. The priority scheme directs resources to selecting contacts who

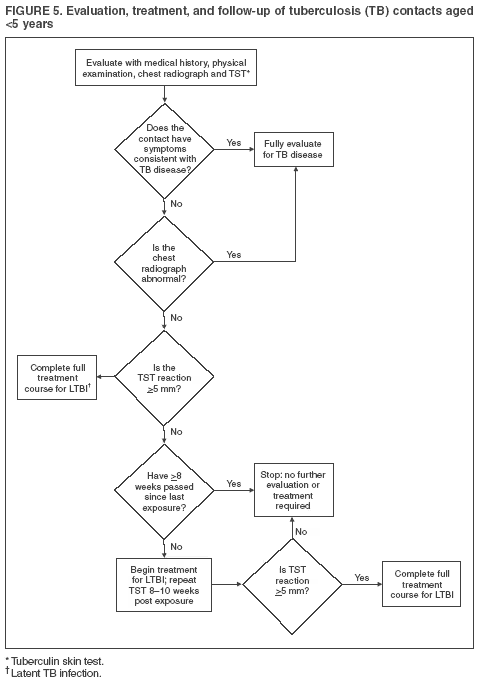

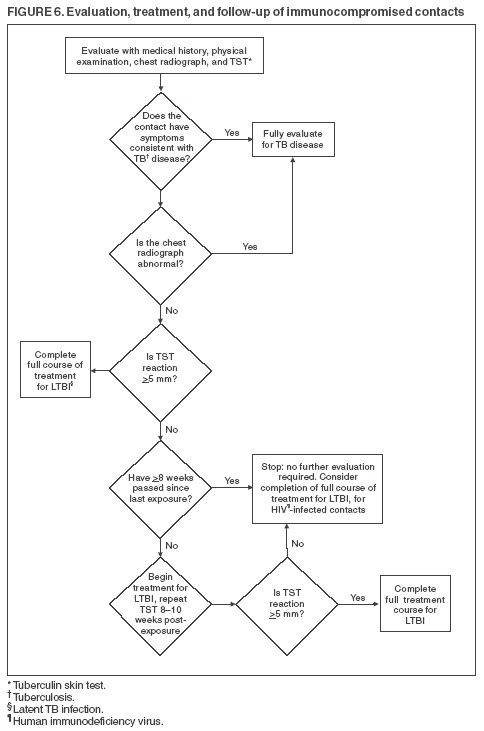

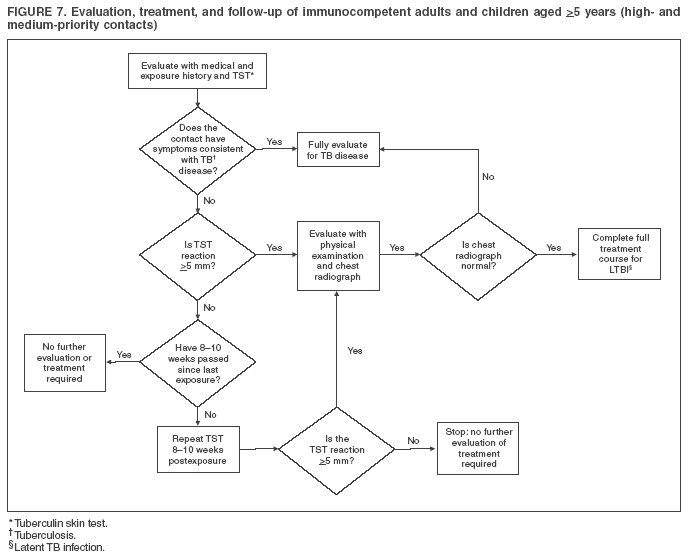

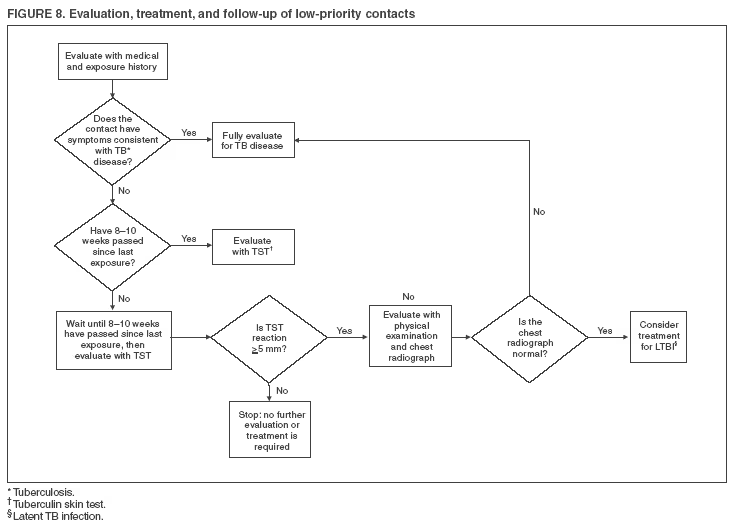

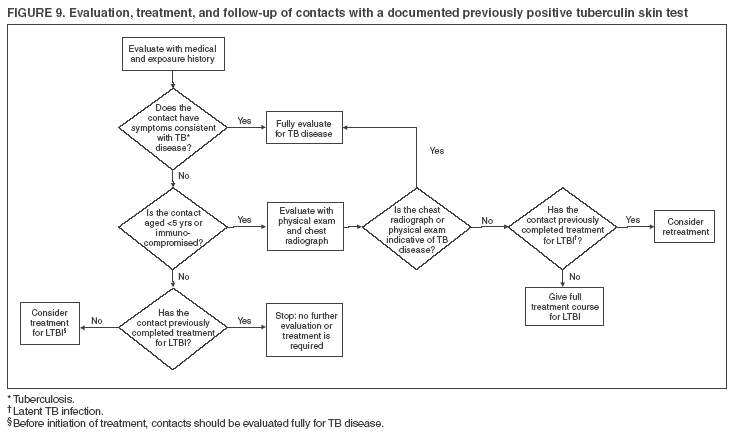

Characteristics of the Index Patient The decision to initiate a contact investigation is determined on the basis of the characteristics of the index patient (see Decisions to Initiate a Contact Investigation). Contacts of a more infectious index patient (e.g., one with AFB sputum smear positive TB) should be assigned a higher priority than those of a less infectious one because contacts of the more infectious patient are more likely to have recent infection or TB disease (19,40,47--50). Characteristics of Contacts Intrinsic and acquired conditions of the contact affect the likelihood of TB disease progression after infection, although the predictive value of certain conditions (e.g., being underweight for height) is imprecise as the sole basis for assigning priorities (51,52). The most important factors are age <5 years and immune status. Other medical conditions also might affect the probability of TB disease after infection. Age. After infection, TB disease is more likely to occur in younger children; the incubation or latency period is briefer; and lethal, invasive forms of the disease are more common (53--58). The age-specific incidence of disease for children who have positive skin test results declines through age 4 years (56). Children aged <5 years who are contacts are assigned high priority for investigation. A study of 82,269 tuberculin reactors aged 1--18 years who were control subjects in a Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) trial* in Puerto Rico indicated that peak incidence of TB occurred among children aged 1--4 years (56). Infants and postpubertal adolescents are at increased risk for progression to TB disease if infected, and children aged <4 years are at increased risk for disseminated disease (57). The American Academy of Pediatrics also recommends primary prophylaxis for children aged <4 years (57). Guidelines published by ATS and CDC recommend primary prophylaxis for children aged <5 years (6,59). These guidelines are consistent with previous CDC recommendations in setting the cut-off at age <5 years for assigning priority and recommending primary prophylaxis (6,59). Immune status. HIV infection results in the progression of M. tuberculosis infection to TB disease more frequently and more rapidly than any other known factor, with disease rates estimated at 35--162 per 1,000 person-years of observation and a greater likelihood of disseminated and extrapulmonary disease (60--64). HIV-infected contacts are assigned high priority, and, starting at the time of the initial encounter, extra vigilance for TB disease is recommended. Contacts receiving >15 mg of prednisone or its equivalent for >4 weeks also should be assigned high priority (6). Other immunosuppressive agents, including multiple cancer chemotherapy agents, antirejection drugs for organ transplantation, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-a) antagonists, increase the likelihood of TB disease after infection; these contacts also are assigned a high priority (65). Other medical conditions. Being underweight for their height has been reported as a weakly predictive factor promoting progression to TB disease (66); however, assessing weight is not a practical approach for assigning priorities. Other medical conditions that can be considered in assigning priorities include silicosis, diabetes mellitus, and status after gastrectomy or jejunoileal bypass surgery (67--76). Exposure. Air volume, exhaust rate, and circulation predict the likelihood of transmission in an enclosed space. In large indoor settings, because of diffusion and local circulation patterns, the degree of proximity between contacts and the index patient can influence the likelihood of transmission. Other subtle environmental factors (e.g., humidity and light) are impractical to incorporate into decision making. The terms "close" and "casual," which are frequently used to describe exposures and contacts, have not been defined uniformly and therefore are not useful for these guidelines. The most practical system for grading exposure settings is to categorize them by size (e.g., "1" being the size of a vehicle or car, "2" the size of a bedroom, "3" the size of a house, and "4" a size larger than a house [16]). This has the added advantage of familiarity for the index patient and contacts, which enables them to provide clearer information. The volume of air shared between an infectious TB patient and contacts dilutes the infectious particles, although this relationship has not been validated entirely by epidemiologic results (15,77--79). Local circulation and overall room ventilation also dilute infectious particles, but both factors can redirect exposure into spaces that were not visited by the index patient (80--83). These factors have to be considered. The likelihood of infection depends on the intensity, frequency, and duration of exposure (16,17,40,84). For example, airline passengers who are seated for >8 hours in the same or adjoining row as a person who is contagious are much more likely to be infected than other passengers (85--88). One set of criteria for estimating risk after exposure to a person with pulmonary TB without lung cavities includes a cut-off of 120 hours of exposure per month (84). However, for any specific setting, index patient, and contacts, the optimal cut-off duration is undetermined. Administratively determined durations derived from local experience are recommended, with frequent reassessments on the basis of results. Classification of Contacts Priorities for contact investigation are determined on the basis of the characteristics of the index patient, susceptibility and vulnerability of contacts, and circumstances of the exposures (Figures 2--4). Any contacts who are not classified as high or medium priority are assigned a low priority. Because priority assignments are practical approximations derived from imperfect information, priority classifications should be reconsidered throughout the investigation as findings are analyzed (see When to Expand a Contact Investigation). Diagnostic and Public Health Evaluation of ContactsOn average, 10 contacts are listed for each person with a case of infectious TB in the United States (50,59,89). Approximately 20%--30% of all contacts have LTBI, and 1% have TB disease (50). Of those contacts who ultimately will have TB disease, approximately half acquire disease in the first year after exposure (90,91). For this reason, contact investigations constitute a crucial prevention strategy. Identifying TB disease and LTBI efficiently during an investigation requires identifying, locating, and evaluating high- and medium-priority contacts who are most at risk. Because they have legally mandated responsibilities for disease control, health departments should establish systems for comprehensive TB contact investigations. In certain jurisdictions, legal measures are in place to ensure that evaluation and follow-up of contacts occur. The use of existing communicable disease laws that protect the health of the community (if applicable to contacts) should be considered for contacts who decline examinations, with the least restrictive measures applied first. Initial Assessment of ContactsDuring the initial contact encounter, which should be accomplished within 3 working days of the contact having been listed the investigation, the investigator gathers background health information and makes a face-to-face assessment of the person's health. Administering a skin test at this time accelerates the diagnostic evaluation. The health department record should include:

Contacts who do not know their HIV-infection status should be offered HIV counseling and testing. Each contact should be interviewed regarding social, emotional, and practical matters that might hinder their participation (e.g., work or travel). When initial information has been collected, priority assignments should be reassessed for each contact, and a medical plan for diagnostic tests and possible treatment can be formulated for high- and medium-priority contacts. Low-priority contacts should not be included unless resources permit and the program is meeting its performance goals. In 2002, for the first time, the percentage of TB patients who were born outside the United States was >50%; this proportion continues to increase (92). Because immigrants are likely to settle in communities in which persons of similar origin reside, multiple contacts of foreign-born index patients also are foreign born. Contacts who come from countries where both BCG vaccination and TB are common are more likely than other immigrants to have positive skin tests results when they arrive in the United States. They also are more likely to demonstrate the booster phenomenon on a postexposure test (17,40). Although valuable in preventing severe forms of disease in young children in countries where TB is endemic, BCG vaccination provides imperfect protection and causes tuberculin sensitivity in certain recipients for a variable period of time (93,94). TSTs cannot distinguish reactions related to remote infection or BCG vaccination from those caused by recent infection with M. tuberculosis; boosting related to BCG or remote infection compounds the interpretation of positive results (95). A positive TST in a foreign-born or BCG-vaccinated person should be interpreted as evidence of recent M. tuberculosis infection in contacts of persons with infectious cases. These contacts should be evaluated for TB disease and offered a course of treatment for LTBI. Voluntary HIV Counseling, Testing, and ReferralApproximately 9% of TB patients in the United States have HIV infection at the time of TB diagnosis, with 16% of TB patients aged 25--44 years having HIV infection (96). In addition, an estimated 275,000 persons in the United States are unaware they have HIV infection (97). The majority of TB contacts have not been tested for HIV infection (98). Contacts of HIV-infected index TB patients are more likely to be HIV infected than contacts of HIV-negative patients (99). Voluntary HIV counseling, testing, and referral for contacts are key steps in providing optimal care, especially in relation to TB (100,101). Systems for achieving convenient HIV-related services require collaboration with health department HIV-AIDS programs. This also can improve adherence to national guidance for these activities (100). Tuberculin Skin TestingAll contacts classified as having high or medium priority who do not have a documented previous positive TST result or previous TB disease should receive a skin test at the initial encounter. If that is not possible, then the test should be administered <7 working days of listing high-priority contacts and <14 days of listing medium-priority contacts. For interpreting the skin test reaction, an induration transverse diameter of >5 mm is positive for any contact (1) Serial tuberculin testing programs routinely administer a two-step test at entry into the program. This detects boosting of sensitivity and can avoid misclassifying future positive results as new infections. The two-step procedure typically should not be used for testing contacts; a contact whose second test result is positive after an initial negative result should be classified as recently infected. Postexposure Tuberculin Skin Testing Among persons who have been sensitized by M. tuberculosis infection, the intradermal tuberculin from the skin test can result in a delayed-type (cellular) hypersensitivity reaction. Depending on the source of recommendations, the estimated interval between infection and detectable skin test reactivity (referred to as the window period) is 2--12 weeks (6,95). However, reinterpretation of data collected previously indicates that 8 weeks is the outer limit of this window period (46,102--106). Consequently, NTCA and CDC recommend that the window period be decreased to 8--10 weeks after exposure ends. A negative test result obtained <8 weeks after exposure is considered unreliable for excluding infection, and a follow-up test at the end of the window period is therefore recommended. Low-priority contacts have had limited exposure to the index patient and a low probability of recent infection; a positive result from a second skin test among these contacts would more likely represent boosting of sensitivity. A single skin test, probably at the end of the window period, is preferred for these contacts. However, diagnostic evaluation of any contact who has TB symptoms should be immediate, regardless of skin test results. Nonspecific or remote delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) response to tuberculin (PPD in the skin test) occasionally wanes or disappears over time. Subsequent TSTs can restore responsiveness; this is called boosting or the booster phenomenon (95,107). For contacts who receive two skin tests, the booster phenomenon can be misinterpreted as evidence of recent infection. This misinterpretation is more likely to occur for foreign-born contacts than it is for those born in the United States (17,108). Skin test conversion refers to a change from a negative to a positive result. To increase the relative certainty that the person has been infected with M. tuberculosis in the interval between tests, the standard U.S. definition for conversion includes a maximum time (2 years) between skin tests and a minimum increase (10 mm) in reaction size (6,34). With the 5 mm cut-off size used for interpreting any single skin test result obtained in contact investigations, the standard definition for conversion typically is irrelevant. For these guidelines, contacts who have a positive result after a previous negative result are said to have had a change in tuberculin status from negative to positive. Medical EvaluationAll contacts whose skin test reaction induration diameter is >5 mm or who report any symptoms consistent with TB disease should undergo further examination and diagnostic testing for TB (6), starting typically with a chest radiograph. Collection of specimens for mycobacteriologic testing (e.g., sputa) is decided on a case-by-case basis and is not recommended for healthy contacts with normal chest radiographs. All contacts who are assigned a high priority because of special susceptibility or vulnerability to TB disease should undergo further examination and diagnostic testing regardless of whether they have a positive skin test result or are ill. Evaluation and Follow-Up of Specific Groups of ContactsBecause children aged <5 years are more susceptible to TB disease and more vulnerable to invasive, fatal forms of TB disease, they are assigned a high priority as contacts and should receive a full diagnostic medical evaluation, including a chest radiograph (Figure 5). If an initial skin test induration diameter is <5 mm and the interval since last exposure is <8 weeks, treatment for presumptive M. tuberculosis infection (i.e., window prophylaxis) is recommended after TB disease has been excluded by medical examination. After a second skin test administered 8--10 weeks postexposure, the decision to treat is reconsidered. If the second test result is negative, treatment should be discontinued and the child, if healthy, should be discharged from medical supervision. If the second result is positive, the full course of treatment for latent M. tuberculosis infection should be completed. Contacts with immunocompromising conditions (e.g., HIV infection) should receive similar care (Figure 6). In addition, even if a TST administered >8 weeks after the end of exposure yields a negative result, a full course of treatment for latent M. tuberculosis infection is recommended after a medical evaluation to exclude TB disease (16). The decision to administer complete treatment can be modified by other evidence concerning the extent of transmission that was estimated from the contact investigation data. The majority of other high- or medium priority contacts who are immunocompetent adults or children aged >5 years can be tested and evaluated as described (Figure 7). Treatment is recommended for contacts who receive a diagnosis of latent M. tuberculosis infection. Evaluation of low-priority contacts who are being tested can be scheduled with more flexibility (Figure 8). The skin test may be delayed until after the window period, thereby negating the need for a second test. Treatment is also recommended for these contacts if they receive a diagnosis of latent M. tuberculosis infection. The risk for TB disease is undetermined for contacts with documentation of a previous positive TST result (whether infection was treated) or TB disease (Figure 9). Documentation is recommended before making decisions from a contact's verbal report. Contacts who report a history of infection or disease but who do not have documentation are recommended for the standard algorithm (Figure 8). Contacts who are immunocompromised or otherwise susceptible are recommended for diagnostic testing to exclude TB disease and for a full course of treatment for latent M. tuberculosis infection after TB disease has been excluded, regardless of their previous TB history and documentation. Healthy contacts who have a documented previous positive skin test result but have not been treated for LTBI can be considered for treatment as part of the contact investigation. Any contact who is to be treated for LTBI should have a chest radiograph to exclude TB disease before starting treatment. Certain guidance regarding collecting historic information from TB patients or contacts stipulates confirmation of previous TST results (e.g., a documented result from a TST) (4). The decision regarding requiring documentation for a specific detail involves a subtle balance. Memory regarding medical history might be weak or distorted, even among medically trained persons. However, the accuracy of details reported by a TB patient or contact might not be relevant for providing medical care or collecting data. For previous TST results, patients can be confused regarding details from their history; routine skin tests sometimes are administered at the same time as vaccinations, and foreign-born patients might confuse a skin test with BCG vaccination or streptomycin injections. For contacts (but not patients with confirmed TB), a skin test result is critical, and documentation of a previous positive result should be obtained before omitting the skin test from the diagnostic evaluation. Treatment for Contacts with LTBIThe direct benefits of contact investigations include 1) finding additional TB disease cases (thus potentially interrupting further transmission) and 2) finding and treating persons with LTBI. One of the national health objectives for 2010 (objective no. 14-13) is to complete treatment in 85% of contacts who have LTBI (107). However, reported rates of treatment initiation and completion have fallen short of national objectives (17,50,109,110). To increase these rates, health department TB control programs must invest in systems for increasing the numbers of infected contacts who are completely treated. These include 1) focusing resources on the contacts most in need of treatment; 2) monitoring treatment, including that of contacts who receive care outside the health department; and 3) providing directly observed therapy (DOT), incentives, and enablers. Contacts identified as having a positive TST result are regarded as recently infected with M. tuberculosis, which puts them at heightened risk for TB disease (6,7). Moreover, contacts with greater durations or intensities of exposure are more likely both to be infected and to have TB disease if infected. A focus first on high-priority and next on medium-priority contacts is recommended in allocating resources for starting and completing treatment of contacts. Decisions to treat contacts who have documentation of a previous positive skin test result or TB disease for presumed LTBI must be individualized because their risk for TB disease is unknown. Considerations for the decision include previous treatment for LTBI, medical conditions putting the contact at risk for TB disease, and the duration and intensity of exposure. Treatment of presumed LTBI is recommended for all HIV-infected contacts in this situation (after TB disease has been excluded), whether they received treatment previously. Window-Period ProphylaxisTreatment during the window period (see Diagnostic and Public Health Evaluation of Contacts) has been recommended for susceptible and vulnerable contacts to prevent rapidly emerging TB disease (4,6,56,61,111). The evidence for this practice is inferential, but all models and theories support it. Groups of contacts who are likely to benefit from a full course of treatment (beyond just window-period treatment) include those with HIV infection, those taking immunosuppressive therapy for organ transplantation, and persons taking TNF-a antagonists (6,61,62,65). The risks for TB are less clear for patients who chronically take the equivalent of >15 mg per day of prednisone (6). TB disease having been ruled out, prophylactic treatment of presumed M. tuberculosis infection is recommended as an option for all these groups. The decision as to whether to treat individual contacts who have negative skin test results should take into consideration two factors:

Guidelines for providing care to contacts of drug-resistant TB patients and selecting treatment regimens have been published (6,7,112). Drug susceptibility results for the M. tuberculosis isolate from the index patient (i.e., the presumed source of infection) are necessary for selecting or modifying the treatment regimen for the exposed contact. Resistance only to INH among the first line agents leaves the option of 4 months of daily rifampin. Additional resistance to rifampin constitutes MDR TB. None of the potential regimens for persons likely infected with MDR TB has been tested fully for efficacy, and these regimens are often poorly tolerated. For these reasons, consultation with a physician with expertise in this area is recommended for selecting or modifying a regimen and managing the care of contacts (6). Contacts who have received a diagnosis of infection attributed to MDR TB should be monitored for 2 years after exposure; guidelines for monitoring these contacts have been published previously (6). Adherence to TreatmentOne of the national health objectives for 2010 is to achieve a treatment completion rate of 85% for infected contacts who start treatment (objective no. 14-13) (107). However, operational studies indicate that this objective is not being achieved (17,110). Although DOT improves completion rates (17), it is a resource-intensive intervention that might not be feasible for all infected contacts. The following order of priorities is recommended when selecting contacts for DOT (including window-period prophylaxis):

Checking monthly or more often for adherence and adverse effects of treatment by home visits, pill counts, or clinic appointments is recommended for contacts taking self-supervised treatment. All contacts being treated for infection should be evaluated in person by a health-care provider at least monthly. Incentives (e.g., food coupons or toys for children) and enablers (e.g., transportation vouchers to go to the clinic or pharmacy) are recommended as aids to adherence. Incentives provide simple rewards whereas enablers increase a patient's opportunities for adherence. Education regarding TB, its treatment, and the signs of adverse drug effects should be part of each patient encounter. When to Expand a Contact InvestigationA graduated approach to contact investigations (i.e., a concentric circles model) has been recommended previously (4,5,113). With this model, if data indicate that contacts with the greatest exposure have an infection rate greater than would be expected in their community, contacts with progressively less exposure are sought. The contact investigation would expand until the rate of positive skin test results for the contacts was indistinguishable from the prevalence of positive results in the community (5). In addition to its simplicity and intuitive appeal, an advantage to this approach is that contacts with less exposure are not sought until evidence of transmission exists. Disadvantages are that 1) surrogates for estimating exposure (e.g., living in the same household) often do not predict the chance of infection, 2) the susceptibility and vulnerability of contacts are not accommodated by the model, and 3) the estimated prevalence for tuberculin sensitivity in a specific community generally is unknown. In addition, when the prevalence for a community is known but is substantial (e.g., >10%), the end-point for the investigation is obscured. Recent operational studies indicate that health departments are not meeting their objectives for high- and medium-priority contacts (17,50,109). In these settings, contact investigations generally should not be expanded beyond high- and medium-priority contacts. However, if data from an investigation indicate more transmission than anticipated, more contacts might need to be included. When determining whether to expand the contact investigation, consideration of the following factors is recommended:

In the absence of evidence of recent transmission, an investigation should not be expanded to lower priority contacts. When program-evaluation objectives are not being achieved, a contact investigation should be expanded only in exceptional circumstances, generally those involving highly infectious persons with high rates of infection among contacts or evidence for secondary cases and secondary transmission. Expanded investigations must be accompanied by efforts to ensure completion of therapy. The strategy for expanding an investigation should be derived from the data obtained from the investigation previously (4,5,43). The threshold for including a specific contact thereby is decreased. As in the initial investigation, results should be reviewed at least weekly so the strategy can be reassessed. At times, results from an investigation indicate a need for expansion that available resources do not permit. In these situations, seeking consultation and assistance from the next higher level in public health administration (e.g., the county health department consults with the state health department) is recommended. Consultation offers an objective review of strategy and results, additional expertise, and a potential opportunity to obtain personnel or funds for meeting unmet needs. Communicating Through the MediaRoutine contact investigations, which have perhaps a dozen contacts, are not usually considered newsworthy. However, certain contact investigations have potential for sensational coverage and attract attention from the media. Typical examples include situations involving numerous contacts (especially children), occurring in public settings (e.g., schools, hospitals, prisons), occurring in workplaces, associated with TB fatalities, or associated with drug-resistant TB. Reasons for Participating in Media CoverageMedia coverage can provide both advantages and drawbacks for the health department, and careful planning is recommended before communicating with reporters. Favorable, accurate coverage

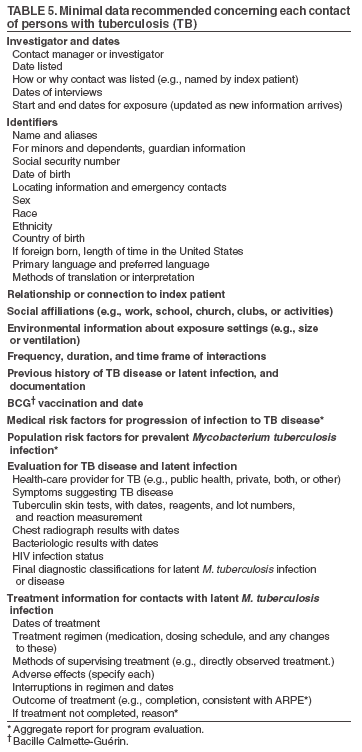

Potential drawbacks of media coverage are that such coverage can

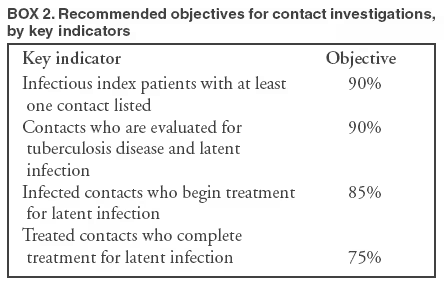

Anticipatory preparation of clear media messages, coordinated among all parties for clarity and consistency, is recommended. The majority of health departments have formal policies and systems for arranging media communications, and TB control officials are advised to work with their media-communications services in securing training and preparing media messages anticipating news coverage. In certain instances, this will require coordination among local, state, and federal public health organizations. Issuing a press release in advance of any other media coverage is recommended so as to provide clear, accurate messages from the start. Waiting until a story reaches the media through other sources leaves the health department reacting to inaccuracies in the story and could lend credence to a perception that information is being withheld from the public. Certain newsworthy contact investigations involve collaborators outside of the health department because of the setting (e.g., a homeless shelter). The administrators of these settings are likely to have concerns, distinct from the public health agenda, regarding media coverage. For example, a hospital administrator might worry that reports of suspected TB exposures in the hospital will create public distrust of the hospital. Collaboration on media messages is a difficult but necessary part of the overall partnership between the hospital (in this example) and the health department. Early discussions regarding media coverage are recommended for reducing later misunderstandings. In addition, development of a list of communication objectives also is recommended in preparing for media inquiries. Data Management and Evaluation of Contact InvestigationsData collection related to contact investigations has three broad purposes: 1) management of care and follow-up for individual index patients and contacts, 2) epidemiologic analysis of an investigation in progress and investigations overall, and 3) program evaluation using performance indicators that reflect performance objectives. A systematic, consistent approach to data collection, organization, analysis, and dissemination is required (114--117). Data collection and storage entail both substantial work and an investment in systems to obtain full benefits from the efforts. Selecting data for inclusion requires balancing the extra work of collecting data against the lost information if data are not collected. If data are collected but not studied and used when decisions are made, then data collection is a wasted effort. The most efficient strategy for determining which data to collect is to work back from the intended uses of the data. Reasons Contact Investigation Data Are NeededFor each index patient and the patient's associated contacts, a broad amount of demographic, epidemiologic, historic, and medical information is needed for providing comprehensive care (Tables 2, 4, and 5). In certain instances, such care can last >1 year, so information builds by steps and has numerous longitudinal elements (e.g., number of clinic visits attended, number of treatment doses administered, or mycobacteriologic response to treatment). Data on certain process steps are necessary for monitoring whether the contact investigation is keeping to timeline objectives (e.g., how soon after listing the skin test is administered to a contact). Aggregated data collected during an investigation inform public health officials whether the investigation is on time and complete. The ongoing analysis of data also contributes to reassessment of the strategy used in the investigation (e.g., whether the infection rate was greater for contacts believed to have more exposure). Data from a completed investigation and from all investigations in a fixed period (e.g., 6 months) might demonstrate progress in meeting program objectives (Box 2). However, these core measurements for program evaluation cannot directly demonstrate why particular objectives were not achieved. If the data are structured and stored in formats that permit detailed retrospective review, then the reasons for problems can be studied. CDC's Framework for Program Evaluation in Public Health is recommended for assessing the overall activities of contact investigations (118). Data definitions are crucial for consistency and subsequent mutual comprehension of analytic results. However, detailed definitions that accommodate every contingency defeat the simplicity required for an efficient system. Data definitions are best when they satisfy the most important contingencies. This requires a trade-off between completeness and clarity. As with the initial selection of data, working back from the intended uses of the data is helpful in deciding how much detail the data definitions should have. Routine data collection can indicate whether the priority assignments of contacts were a good match to the final results (e.g., infection rates and achievement of timelines). These data cannot determine whether all contacts with substantial exposure were included in the original list (i.e., whether certain contacts who should have been ranked as high priority were missed completely because of gaps in the investigation). Methods for Data Collection and StorageDirect computer entry of all contact investigation data is recommended. Systems designed to increase data quality (e.g., through use of error checking rules) are preferred. However, technologic and resource limitations are likely to require at least partial use of paper forms and subsequent transfer at a computer console, which requires a greater level of data quality assurance because of potential errors in the transfer. Security precautions for both paper copy and electronically generated data should be commensurate with the confidentiality of the information. Ongoing training concerning systems is recommended for personnel who collect or use the data. A comprehensive U.S. software system for contact investigation data collection and storage has not been implemented. Health department officials are advised to borrow working systems from other jurisdictions that have similar TB control programs. Any system should incorporate these recommendations. Computer storage of data offers improved performance of daily activities because a comprehensive system can provide reminders regarding the care needs of individual contacts (e.g., notification regarding contacts who need second skin tests and recommended dates). A system also can perform interim analysis of aggregate results at prescheduled intervals. This contributes both to reassessment of the investigative strategy (see When to Expand a Contact Investigation) and to program evaluation. Confidentiality and Consent in Contact InvestigationsMultiple laws and regulations protect the privacy and confidentiality of patients' health care information (119). Applicable federal laws include Sections 306 and 308(d) of the Public Health Service Act; the Freedom of Information Act of 1966; the Privacy Act of 1974, which restricts the use of Social Security numbers; the Privacy Protection Act of 1998; and the Privacy Rule of HIPAA, which protects individually identifiable health information and requires an authorization of disclosure (39). Section 164.512 of HIPAA lists exemptions to the need to obtain authorization, which include communicable diseases reported by a public health authority as authorized by law (120). Interrelationships between Federal and State codes are complex, and consultation with health department legal counsel is recommended when preparing policies governing contact investigations. Maintaining confidentiality is challenging during contact investigations because of the social connections between an index patient and contacts. Constant attention is required to maintain confidentiality. Ongoing discussions with the index patient and contacts regarding confidentiality are helpful in finding solutions, and individual preferences often can be accommodated. Legal and ethical issues in sharing confidential information sometimes can be resolved by obtaining consent from the patient to disclose information to specified persons and by documenting this consent with a signed form. The index patient might not know the names of contacts, and contacts might not know the index patient by name. With the patient's consent, a photograph of the patient or of contacts might be a legal option to assist in identifying contacts. In certain places, separate consent forms are required for taking the photograph and for sharing it with other persons. In congregate settings, access to occupancy rosters might be necessary to identify exposed contacts in need of evaluation. In their approach to confidentiality and consent issues for contact investigations, TB control programs will need to address the following:

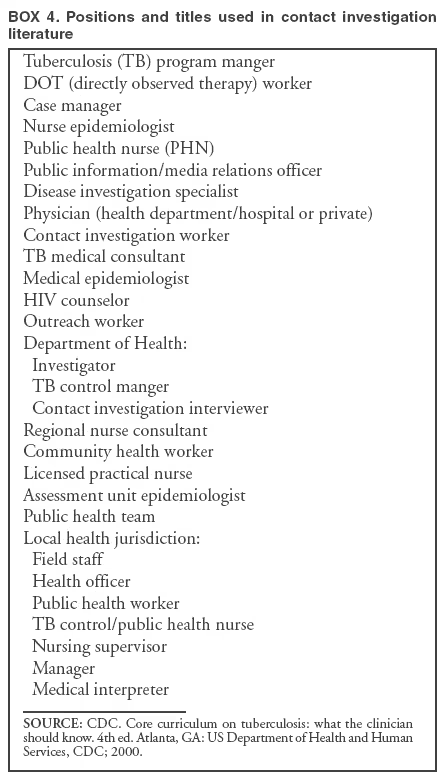

Staffing and Training for Contact Investigations The multiple interrelated tasks in a contact investigation require personnel in the health department and other health-care-delivery systems to fulfill multiple functions and skills (Box 3). Training and continuous on-the-job supervision in all these functions help ensure successful contact investigations. Job titles of personnel who conduct contact investigations vary among jurisdictions (Box 4). State licensing boards and other authorities govern the scope of practice of health department personnel, and this narrows the assignment of functions. Reflection of these licensure-governed functions is recommended for personnel position descriptions, with specific references to contact investigations as duties. Contact Investigations in Special CircumstancesContact investigations frequently involve multiple special circumstances, but these circumstances typically are not of substantive concern. This section lists special challenges and suggests how the general guidance in other sections of this document can be adapted in response. OutbreaksA TB outbreak indicates potential extensive transmission. An outbreak implies that 1) a TB patient was contagious, 2) contacts were exposed for a substantial period, and 3) the interval since exposure has been sufficient for infection to progress to disease. An outbreak investigation involves several overlapping contact investigations, with a surge in the need for public health resources. More emphasis on active case finding is recommended, which can result in more contacts than usual having chest radiographs and specimen collection for mycobacteriologic assessment. Definitions for TB outbreaks are relative to the local context. Outbreak cases can be distinguished from other cases only when certain association in time, location, patient characteristics, or M. tuberculosis attributes (e.g., drug resistance or genotype) become apparent. In low-incidence jurisdictions, any temporal cluster is suspicious for an outbreak. In places where cases are more common, clusters can be obscured by the baseline incidence until suspicion is triggered by a noticeable increase, a sentinel event (e.g., pediatric cases), or genotypically related M. tuberculosis isolates. On average in the United States, 1% of contacts (priority status not specified) have TB disease at the time that they are evaluated (50). This disease prevalence is >100 times greater than that predicted for the United States overall. Nonetheless, this 1% average rate is not helpful in defining outbreaks, because substantial numbers of contacts are required for a statistically meaningful comparison to the 1% average. A working definition of "outbreak" is recommended for planning investigations. A recommended definition is a situation that is consistent with either of two sets of criteria: